It’s a story of corporate courtship, a brief period of “magical” synergy, and a cold-blooded boardroom coup that fundamentally reshaped the trajectory of personal computing. At the heart of this drama stood two men: the visionary co-founder Steve Jobs and the seasoned marketing executive John Sculley.

The Seduction: From Sugar Water to Silicon

By 1983, Apple was no longer a hobbyist’s garage project; it was a public company facing fierce competition from IBM. Steve Jobs, while brilliant, was perceived by the board as too young and volatile to lead a multinational corporation. They wanted “adult supervision.”

Jobs set his sights on John Sculley, the then-president of PepsiCo. Sculley was a marketing prodigy responsible for the “Pepsi Challenge.” The recruitment process was a months-long pursuit that culminated in one of the most famous lines in business history. When Sculley initially hesitated, Jobs challenged him:

“Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?”

Steve Jobs challenges John Sculles

Jobs wanted Sculley to share his excitement about the Macintosh and showed him a prototype. “This product means more to me than anything I’ve done,” Jobs said. “I want you to be the first person outside of Apple to see it.” He dramatically pulled the prototype out of a vinyl bag and gave a demonstration. Sculley found Jobs as memorable as his machine. “He seemed more a showman than a businessman. Every move seemed calculated, as if it was rehearsed, to create an occasion of the moment.”

Jobs had asked Software Developer Andy Hertzfeld and the gang to prepare a special screen display for Sculley’s amusement. “He’s really smart,” Jobs said. “You wouldn’t believe how smart he is.” The explanation that Sculley might buy a lot of Macintoshes for Pepsi “sounded a little bit fishy to me,” Hertzfeld recalled, but he and Susan Kare created a screen of Pepsi caps and cans that danced around with the Apple logo. Hertzfeld was so excited he began waving his arms around during the demo, but Sculley seemed underwhelmed. “He asked a few questions, but he didn’t seem all that interested,” Hertzfeld recalled. He never ended up warming to Sculley. “He was incredibly phony, a complete poseur,” he later said. “He pretended to be interested in technology, but he wasn’t. He was a marketing guy, and that is what marketing guys are: paid poseurs.”

Steve Jobs was not very impressed by the concerns of his team and decided to hire the marketing specialist: Sculley joined Apple as CEO in April 1983, bringing the corporate discipline and marketing prowess Apple’s board craved.

John Sculley and Steve Jobs: The “Dynamic Duo” Phase

Initially, the partnership was remarkably harmonious. The media dubbed them the “The Dynamic Duo.”. Jobs was the product visionary, dreaming up the Macintosh; Sculley was the operational expert who knew how to scale a brand.

The Bond: They were nearly inseparable, often finishing each other’s sentences in interviews. Sculley gave Jobs the professional validation he sought, and Jobs gave Sculley a sense of higher purpose beyond consumer goods.

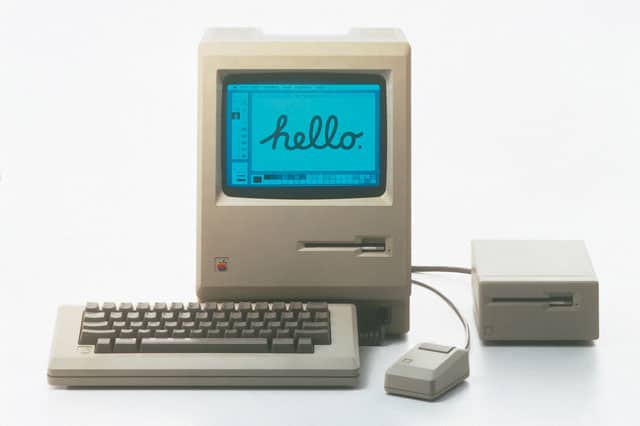

During this honeymoon period, they successfully launched the Macintosh in 1984, backed by the iconic Super Bowl commercial. It seemed, for a moment, that the marriage of counter-culture innovation and Madison Avenue marketing was invincible.

The Apple Macintosh had not been a success from the outset. The hardware was not designed particularly generously for the requirements of a graphical user interface. Especially the main memory had been calculated rather tightly. Moreover, there was no hard disk for the Mac at that time.

“The original 128K Mac had too many problems to list,” wrote Jack Schofield from the Guardian 20 years later in an article about the 20th anniversary of the apple Macintosh. “It had too little software, you couldn’t expand it (no hard drive, no SCSI port, no ADB port, no expansion slots), it was horribly underpowered and absurdly overpriced. The way MacWrite and MacPaint worked together was brilliant, but producing anything more than a short essay was a huge struggle. Just copying a floppy was a nightmare.” In addition, there was a lack of appropriate business software.

The Mac lacked the applications that dragged the Charlie Chaplin figure across the screen box by box in the IBM’s advertising spot for the PC. Therefore, Guy Kawasaki and other “Software Evangelists” of Apple made an effort to convince the developers of other software companies to write programs for the Mac. The Mac’s ROM, which had been calculated far too narrowly at 128 kilobytes, did not make this a simple task. Not until the “Fat Mac” with 512 kilobytes was launched one year after the first Macintosh had this narrow bottleneck been removed.

The problem came to a head when by the beginning of 1985, the Macs that had not found purchasers during the Christmas sales of 1984 were piling up in storage. Apple had to publish the first quarterly loss in the company’s history and release a fifth of the staff. During a marathon meeting on April 10 and 11, 1985, Apple’s CEO John Sculley demanded to have Steve Jobs relieved of his position as an Apple vice president and general manager of the Macintosh department.

According to Sculley’s wishes, Steve Jobs was to represent the company externally as a new Apple chairman without influencing the core business. As Jobs got wind of these plans to deprive him of his power, he tried to arrange a coup against Sculley on the Apple board. Sculley told the board: “I’m asking Steve to step down and you can back me on it and then I take responsibility for running the company, or we can do nothing and you’re going to find yourselves a new CEO.” The majority of the board backed the ex-Pepsi man and turned away from Steve Jobs.

On May 31, 1985, Jobs lost his responsibilities and was shuffled off to the chairman position. In September, the Apple co-founder left the company with a few people in order to found NeXT Computer. “I feel like somebody just punched me in the stomach and knocked all my wind out. I’m only 30 years old and I want to have a chance to continue creating things. I know I’ve got at least one more great computer in me. And Apple is not going to give me a chance to do that,” Jobs wrote to Mike Markkula on parting. Ten years later, Steve Jobs also commented on his disempowerment with bitterness in the TV documentary “Triumph of the Nerds” (1996):

Excerpt from the TV documentary “Triumph of the Nerds” with Robert Cringley

Jobs: What can I say? I hired the wrong guy. –

Question: That was Sculley?

Jobs: Yeah and he destroyed everything I spent ten years working for. Starting with me but that wasn’t the saddest part. I would have gladly left Apple if Apple would have turned out like I wanted it to.

Apple’s Heart and Soul

Andy Hertzfeld, one of the Macintosh’s fathers, later recalled the events:

The conflict came to a head at the April 10th board meeting. The board thought they could convince Steve to transition back to a product visionary role, but instead he went on the attack and lobbied for Sculley’s removal. After long wrenching discussions with both of them, and extending the meeting to the following day, the board decided in favor of John, instructing him to reorganize the Macintosh division, stripping Steve of all authority. Steve would remain the chairman of Apple, but for the time being, no operating role was defined for him. John didn’t want to implement the reorganization immediately, because he still thought that he could reconcile with Steve, and get him to buy into the changes, achieving a smooth transition with his blessing. But after a brief period of depressed cooperation, Steve started attacking John again, behind the scenes in a variety of ways. I won’t go into the details here, but eventually John had to remove Steve from his management role in the Macintosh division involuntarily. Apple announced Steve’s removal, along with the first quarterly loss in their history as well as significant layoffs, on Friday, May 31, 1985, Fridays being the traditional time for companies to announce bad news. It was surely one of the lowest points of Apple history.

Hertzfeld mourned for Steve Jobs openly: “Apple never recovered from losing Steve. Steve was the heart and soul and driving force. It would be quite a different place today. They lost their soul.” In contrast, Larry Tessler, who had come to Apple from Xerox, refers to mixed reactions of the Apple staff: “People in the company had very mixed feelings about it. Everyone had been terrorized by Steve Jobs at some point or another and so there was a certain relief that the terrorist had gone but on the other hand I think there was an incredible respect for Steve Jobs by the very same people and we were all very worried – what would happen to this company without the visionary, without the founder without the charisma…”

The Sculley Era: From Visionary Disruption to Corporate Precision

The departure of Steve Jobs in 1985 marked a fundamental shift in Apple’s DNA. While the “Jobsian” approach was rooted in creating “insanely great” products regardless of immediate market demand, John Sculley’s leadership transitioned the company toward a market-driven, high-margin business model.

Embracing the “Open” Mac

One of the most significant shifts was the reversal of Jobs’s “closed box” philosophy. Jobs famously insisted that the Macintosh should be a sealed appliance, devoid of expansion slots, to maintain total control over the user experience.

Sculley, listening to corporate customers, greenlit the Macintosh II (1987). It featured color graphics and expansion slots. This move was a massive commercial success, as it allowed the Mac to compete with IBM in the high-end workstation market.

The Desktop Publishing Revolution

Under Sculley, Apple stopped trying to sell the Mac as a general-purpose “appliance for the rest of us” and found its “killer app”: Desktop Publishing (DTP).

By pairing the Macintosh with the LaserWriter printer and Aldus PageMaker software, Sculley targeted a specific niche—graphic designers and publishers. This strategy saved the company, creating a loyal, high-paying user base that allowed Apple to charge premium prices during the late 80s.

Milking the Apple II “Cash Cow”

While Jobs had viewed the Apple II as an obsolete distraction, Sculley recognized it was the company’s financial lifeblood. He continued to iterate on the line (notably the Apple IIGS), using the profits from the aging platform to fund the expensive research and development of future Macintosh models. This pragmatism provided the stability Apple needed to survive the mid-80s tech slump.

The PowerBook Triumph

In 1991, Apple released the PowerBook, arguably the most successful product of the Sculley years. While Jobs’s earlier attempt at a portable (the 1989 Macintosh Portable) was a 16-pound failure, the PowerBook was a masterpiece of industrial design. It introduced the ergonomic layout we still see in laptops today—the keyboard pushed back to provide palm rests and a centered pointing device (the trackball). It captured 40% of the laptop market at its peak.

Strategy by Proliferation (The Downfall)

However, the post-Jobs era also saw the beginning of “product sprawl.” Without Jobs’s obsessive focus, the product line became bloated. Apple began releasing dozens of confusingly named models—Performa, Centris, Quadra—often with nearly identical specs. This led to:

- Customer Confusion: It was impossible for a buyer to know which Mac was right for them.-

- Inventory Bloat: Managing so many different hardware configurations became a logistical nightmare.

- Brand Dilution: Apple started to look like just another PC manufacturer, losing its “special” status.

The Newton: A Visionary Leap Too Soon

Sculley’s final major push was the Apple Newton (MessagePad). He coined the term “Personal Digital Assistant” (PDA) and envisioned a world of handheld computing. However, without Jobs’s perfectionism, the product was launched prematurely. The handwriting recognition—its core feature—was unreliable, turning the device into a punchline in popular culture.

The immediate post-Jobs era was characterized by professionalization. Sculley turned Apple into a highly profitable, organized, and respected corporate entity. However, the cost was the loss of a singular, coherent vision. By the early 1990s, Apple was a company that made great hardware but had lost its way. Even before Microsoft introduced Windows 95, Apple sales were under heavy pressure. In 1993 Sculley had to step down.

Searching for a Strategy of Survival

Michael Spindler, known as “The Diesel” for his work ethic, took the helm after Sculley. His tenure was marked by a desperate attempt to keep Apple relevant in a world increasingly dominated by Microsoft’s Windows. Spindler successfully oversaw the architectural shift from Motorola 68k processors to the PowerPC. While technically impressive, it was an expensive and exhausting transition for developers and users alike. But Spindler made ohne bis mistake: In a move that Steve Jobs would later describe as “selling the soul of the company,” Spindler licensed the Macintosh Operating System to third-party manufacturers (cloners). The goal was to increase market share, but instead, it cannibalized Apple’s own high-margin hardware sales. Michael Spindler resigned as CEO of Apple on January 31, 1996. His departure followed a period of severe financial struggle for the company, including a massive quarterly loss and a failed attempt to sell Apple to Sun Microsystems.

The Amelio Era: 500 Days of Crisis

When Gil Amelio took over in 1996, Apple was hemorrhaging cash. The company was suffering from massive quarterly losses and a bloated product line that lacked any clear direction. Apple’s greatest asset, the Mac OS, was aging rapidly. It lacked modern features like protected memory and multitasking. Amelio realized that Apple could not build a new operating system in-house fast enough (the internal “Copland” project had failed).

Amelio began looking for an external operating system to buy. It is an irony of computer history that Jobs later saved the struggling Apple Computer company. NeXT’s subsequent 1997 buyout by Apple brought Jobs back to the company he co-founded, and he has served as its CEO since then. Jobs did not only save Apple, but revolutionized the world with the iMac, the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad.

Steve Jobs and John Sculley: Not on good terms

In an Interview (June 2010) Sculley credits Jobs for everything Apple has accomplished and still laments the way things turned out. “I haven’t spoken to Steve in 20-odd years,” Sculley told The Daily Beast. “Even though he still doesn’t speak to me, and I expect he never will, I have tremendous admiration for him.”

Sculley said in the interview he accepts responsibility for his role but also believes that Apple’s board should have understood that Jobs needed to be in charge. “My sense is that it probably would never have broken down between Steve and me if we had figured out different roles,” Sculley said. “Maybe he should have been the CEO and I should have been the president. It should have been worked out ahead of time, and that’s one of those things you look to a really good board to do.”