It All Began with “Annie” – The Vision of a Computer for the Masses

(Updated: May 2018)

It had been a long way until the day of the official introduction of the Macintosh on January 24th, 1984. Five years earlier, in spring 1979, Apple chairman Mike Markkula wondered whether his company should bring a 500 dollar computer to market. Markkula then charged Jef Raskin with the secret “Annie” project.

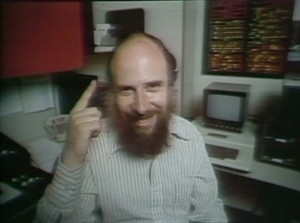

Raskin was a “philosophical guy who could be both playful and ponderous”, writes Walter Isaacson in his book “Steve Jobs”. Raskin had studied computer science, taught music and visual arts, conducted a chamber opera company, and organized guerrilla theater. His 1967 doctoral thesis at U.C. San Diego argued that computers should have graphical rather than text-based interfaces.

Raskin had been responsible for Apple’s publications, particularly manuals, and actually was to more intensely oversee the developers writing the applications for the Apple II. “I told him [Markkula] it was a fine project, but I wasn’t terribly interested in a 500-dollar game machine,” Raskin later remembered. “However, there was this thing that I’d been dreaming about – it was [that] it would be designed from a human factors perspective, which at that time was totally incomprehensible.”

In fall 1979, Raskin wrote his article “Computers by the Millions“, in which he drafted his version of a computer for the masses. Markkula insisted on the report to be treated as a confidential internal report. The essay was not published until 1982 in the SIGPC Newsletter, Vol. 5, No. 2.

Raskin had chosen a completely new approach, because until then, the “technically feasible” is what defined a computer’s design. The academic computer scientist, who had kept secret his diploma from the Apple founders at the time of his appointment (as Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs approached academics extremely distrustfully), wanted to design a computer for the normal person in the street – which of course could not to be unattainable.

The expression of the “Person in the Street” formed by Raskin became a dictum at Apple – abbreviated as PITS. Raskin’s first draft envisioned a closed computer including monitor, keyboard and printer able to work without any external wires – and all that for 500 dollars. In return, the Macintosh should only be equipped with a tiny five inch display, a cheap CPU (6809) and a main memory calculated extremely tight at 64 kilobytes.

At that time, Steve Jobs had not taken particular interest in the Macintosh project – and due to some dim apprehension, Raskin tried everything to exclude the Apple co-founder. Yet in the summer of 1980, a serious conflict between Jobs and Apple’s president Mike Scott was brewing as Scott intended to edge Jobs out of the concrete development of the new Lisa. With his capricious and at times fairly aggressive management style, Jobs had snubbed many developers. In addition, Scott did not think him capable of a major management role and thus planned to assign him the less important role of a company spokesman and promoter in advance of Apple’s initial public offering on December 12th, 1980.

So, Jobs left the Lisa project – and looked at Jef Raskin’s baby. The Apple co-founder liked the concept of a cheap machine for the mass market, but he didn’t like Raskin’s design. “Jobs was enthralled by Raskin’s vision, but not by his willingness to make compromises to keep down the cost,” writes Isaacson. At one point in the fall of 1979 Jobs told him instead to focus on building what he repeatedly called an “insanely great” product. “Don’t worry about price, just specify the computer’s abilities,” Jobs told him. Raskin responded with a sarcastic memo. It spelled out everything you would want in the proposed computer: a high-resolution color display, a printer that worked without a ribbon and could produce graphics in color at a page per second, unlimited access to the ARPA net, and the capability to recognize speech and synthesize music, “even simulate Caruso singing with the Mormon tabernacle choir, with variable reverberation.” The memo concluded, “Starting with the abilities desired is nonsense. We must start both with a price goal, and a set of abilities, and keep an eye on today’s and the immediate future’s technology.” In other words, Raskin had little patience for Jobs’ belief that you could distort reality if you had enough passion for your product.

Jobs wanted to switch to the more powerful Motorola 68000 CPU. Raskin demanded a cheaper processor, and lost again. He had to brood and recalculate the cost of the Mac. The disagreements were more than just technical or philosophical; they became clashes of personality. “I think that he likes people to jump when he says jump,” Raskin once said. “I felt that he was untrustworthy, and that he does not take kindly to being found wanting. He doesn’t seem to like people who see him without a halo.” Jobs was equally dismissive of Raskin. “Jef was really pompous,” he said Isaacson. “He didn’t know much about interfaces. So, I decided to nab some of his people who were really good, like Atkinson, bring in some of my own, take the thing over and build a less expensive Lisa, not some piece of junk.”

Jobs asserted his control of the Macintosh group by canceling a brown-bag lunch seminar that Raskin was scheduled to give to the whole company in February 1981. Raskin happened to go by the room anyway and discovered that there were a hundred people there waiting to hear him; Jobs had not bothered to notify anyone else about his cancellation order. So Raskin went ahead and gave a talk, writes Isaacson.

That incident led Raskin to write a blistering memo to Mike Scott, who once again found himself in the difficult position of being a president trying to manage a company’s temperamental cofounder and major stockholder. It was titled “Working for/with Steve Jobs,” and in it Raskin asserted:

He is a dreadful manager… I have always liked Steve, but I have found it impossible to work for him… Jobs regularly misses appointments. This is so well-known as to be almost a running joke… He acts without thinking and with bad judgment… He does not give credit where due… Very often, when told of a new idea, he will immediately attack it and say that it is worthless or even stupid and tell you that it was a waste of time to work on it. This alone is bad management, but if the idea is a good one he will soon be telling people about it as though it was his own.

That afternoon Scott called in Jobs and Raskin for a showdown in front of Markkula. After a short dog fight Raskin was told to take a leave of absence. “They wanted to humor me and give me something to do, which was fine,” Jobs said Isaacson. “It was like going back to the garage for me. I had my own ragtag team and I was in control.”

It is somehow ironic that Jef Raskin was the person who convinced Steve Jobs to visit the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). The scientists over there pioneered the concept of a graphical user interface (GUI). Bitmapping and graphical interfaces became features of Xerox PARC’s prototype computers, such as the Alto, and its object-oriented programming language, Smalltalk. Jef Raskin decided that these features were the future of computing. So, he began urging Jobs and other Apple colleagues to go check out Xerox PARC. Jobs first refused on the grounds that a large corporation couldn’t possibly be doing anything interesting. But in the end Jobs went to Xerox PARC in December 1979 – and was enlightened.

The rest of the story is well known. For Jobs it was a turning-point. Jobs decided that this was the way forward for Apple.

They showed me really three things. But I was so blinded by the first one I didn’t even really see the other two. One of the things they showed me was object orienting programming they showed me that but I didn’t even see that. The other one they showed me was a networked computer system…they had over a hundred Alto computers all networked using email etc., etc., I didn’t even see that. I was so blinded by the first thing they showed me which was the graphical user interface. I thought it was the best thing I’d ever seen in my life. Now remember it was very flawed, what we saw was incomplete, they’d done a bunch of things wrong. But we didn’t know that at the time but still though they had the germ of the idea was there and they’d done it very well and within you know ten minutes it was obvious to me that all computers would work like this some day.

Steve Jobs in “Thriumph of the Nerds”.

Larry Tesler, at this time a scientist at Xerox PARC, once said: “After an hour looking at demos they understood our technology, and what it meant more than any Xerox executive understood after years of showing it to them.” Jobs tried everything to improve the GUI he had seen at PARC for the new Apple Macintosh.

Andy Hertzfeld, one of the leading Software engineers in the Macintosh project, disputes the view, Jef Raskin was the father of the Apple Macintosh. In an interview with CNET Andy called Steve Jobs “The father of the Macintosh”:

Question: How about Jef Raskin?

Answer: Jef Raskin is the single individual who disagrees with the way I’m telling the story, and he was unhappy with the book (How The Mac Was Made) when he first found out about it, and I suspect he’s still unhappy now.

Jef does claim he invented certain key concepts when no one else thinks he did. Jef actually was not around for almost the entire time the Mac was developed. He left the day before I started (in 1981). Jef’s a tremendous individual and he deserves enormous credit for having the original vision for the Macintosh, starting the project and putting together a dynamite, small team. But then he got at odds with the team and left.

Jef had a lot of ideas about how the Macintosh should be, but they’re not in the Macintosh. If you’re interested: Jef, because he left early, by 1985 he had already designed and licensed a computer that does embody all his ideas–it’s called the Canon Cat.

Question: Then who would you consider the father of the Macintosh?

Answer: Steve Jobs is who I would call the father of the Mac. In second place I’d put Burrell Smith and in third place I’d put Bill Atkinson.

In 1982, Jef Raskin founded the company Information Appliance, Inc. in order to realize his original concept of the Macintosh project. The company brought the “SwyftCard” to market, which is a firmware card for the Apple II. The card featured a program package which was also offered on disk as SwyftWare. With the Swyft, Information Appliance later offered a laptop computer, which, however, experienced only moderate commercial success. Raskin licensed the Swyft design to Canon, which constructed the “Canon CAT” on its basis in 1987.

Raskin also blamed Steve Jobs for the failure, since it was Jobs who as the head of NeXT Computer persuaded Canon into giving up the Cat project. However, it was claimed that Cat also fell victim to internal rivalries at Canon.

In his book “The Humane Interface”, Raskin later described his vision of a computer interface constructed for the human being and oriented to human needs – rather than to technology.

On February 26th, 2005, Jef Raskin died at the age of 61 years.