Steve Jobs Discovers the Macintosh Project

With the initial public offering of Apple Computers in December 1980, Steve Jobs became a multimillionaire – however, he possessed neither enough stock to lead Apple Computers alone nor to determine his own position within Apple. By the beginning of 1981, he actually found himself to be without management responsibility over any specific project. To Jef Raskin’s discomfort, he threw himself into the Macintosh project, which had not been taken really seriously by the Apple board of management at that time.

However, Steve Jobs knew what he wanted. He had seen the graphical user interface of the Xerox Alto at Xerox PARC. Instead of green letters on a dark background, white document windows with black text appeared – just like a sheet of paper. Several different fonts could be selected. The graphics board controlled individual pixels on the screen freely. By means of a mouse, a pointer could be moved on the screen in order to mark texts or issue commands. Files were represented by icons on a virtual desktop.

Demo of the Xerox Alto (quoted from: Triumph of the Nerds)

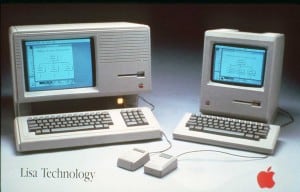

The Alto was not available on the market. For this experimental computer, the main memory alone would have cost about 7,000 dollars at the time. Jobs wanted a computer even better than the Alto – and also better than Apple’s Lisa. However, the new marvelous machine should cost only a fraction of the Lisa’s price, which was about 12,000 dollars, inclusive of external hard disk.

Within Apple, Jobs gathered a small, conniving team – and he did not care for other projects in the company. Andy Hertzfeld, one of the most important software designers in the Macintosh developers team, remembers:

Steve Jobs kind of came bopping by my cubicle saying OK you’re working on the Mac now. And I said well I have to finish up this Apple 2 stuff I’m doing here. No you don’t that stinks that’s not going to amount to anything you gotta start now. And I said well just give me a few days to finish and he said no and what he did was he pulled the plug on my Apple 2 that I was programming just losing, losing the code I’m working on and start taking my computer and walking away with it and what could I do but follow him out to his car cause he had my machine he plopped it down in the trunk and drove me over to this remote building, took the computer out, walked upstairs, plopped it down on a desk, well you’re working on the Mac now. While Jobs pursued his MacMission he needed a more orthodox chief executive to run the company. A respectable face who could sell to corporate America. He chose Pepsi-Cola executive John Sculley. Sculley refused – leave Pepsi for a 4 year old company that had been set up in a garage! Are you serious?! But it was hard saying no to Steve Jobs.

The Macintosh Pirates

Above the roof of “Bandley III”, a pirate flag with the Apple symbol as eye patch was waving – and on deck of the virtual pirate ship, Steve Jobs was standing as a man who wanted to prove it to them all. Jobs’ first victim was Jef Raskin, who had fought against the application of a mouse and instead preferred a pen or a joystick. After Jobs had relieved his opponent of the responsibility for the software, Raskin gave in exasperatedly and left Apple Computers in March 1982. In retrospect, Raskin can claim that he was the first at Apple to have presented the vision of an inexpensive, easy to handle computer for the masses. Yet in order to keep “his” Macintosh below the price limit of 1,500 dollars, Raskin also wanted to make technical compromises which would have put at risk the Mac’s success. Thus, for instance, he insisted on limiting the main memory to a tiny 64 kilobytes. Jobs accomplished 128 kilobytes – and afterwards, even this space was actually far too tight for the system programmers.

Raskin did not particularly support the innovations the Lisa team had picked up in the Xerox PARC and therefore disapproved of the change to the more capable 68000 processor, which was included in the Lisa as well. It is hardly imaginable what would have become of the Mac if Raskin had asserted his extreme parsimony and his resistance to the mouse. After the internal disputes had been settled, the Mac team now fully concentrated on the in-house competition against the far larger Lisa developing team. Beforehand, Jobs had enticed away from the Lisa team ingenious programmers such as Bill Atkinson and Steve Capps.

Love and Hate

As a project manager, Steve Jobs had been highly controversial not only within Apple. “He’s also obnoxious and this comes from his high standards. He has extremely high standards and he has no patience with people who don’t either share those standards or perform to them,“ Bob Metcalfe remembers. He is the inventor of the networking standard Ethernet, who had worked as a researcher in the neighboring research institute Xerox PARC at that time. “He’s also obnoxious and this comes from his high standards. He has extremely high standards and he has no patience with people who don’t either share those standards or perform to them.” However, Metcalfe still thinks a lot of Jobs as he had made the vision created in the Xerox PARC become reality. “Steve Jobs is on my eternal heroes list, there’s nothing he can ever do to get off it.”

The respect for Jobs is also shared by Andy Hertzfeld, who had written the Mac’s kernel in the Macintosh ROM, although he was sometimes afflicted with his boss’s tantrums: – quotation – Kenyon set to work again and shortened the booting process by further three seconds.

In the internal competition at Apple over whether the Lisa or the Macintosh would be finished first, Jobs got the short end of the stick. He lost a personal 5,000 dollar bet against the Lisa team leader John Couch when the Apple business computer was launched in January 1983 – at least one year previous to the Macintosh. However, the Lisa computer soon proved to be a huge flop. With a price of 10,000 dollars (exclusive of hard disk), it was far too expensive;the graphical user interface devoured Lisa’s power such that the computer did not work particularly briskly; and it lacked the necessary programs to induce the business world to buy the Lisa in large numbers. Moreover, the newly established distribution team could hardly resort to any experience in handling Corporate America.

Pingback: 25 Years of Mac - The History of the Apple Macintosh | Mac History

Pingback: The History of the Apple Macintosh » Apple, Macintosh, Jobs, Sculley, Steve, Macs » Mac History

Pingback: The History of the Apple Macintosh » Mac History

Pingback: Piraterie et capitalisme | Le Petit Lexique Colonial

Pingback: το πειρατικό του Steve Jobs | iYannis

Pingback: Safi Bahcall — On Thinking Big, Curing Cancer, and Transforming Industries (#364) – 101 Personal Development

Pingback: Why you shouldn’t buy a Mac in 2020…or maybe ever again. – jonandnic dot com

Pingback: Voice of Ceylon

Pingback: 'Positive deviants': Why rebellious workers spark great ideas - Tastyzz

Pingback: The real significance of Apple’s Macintosh – thequintessentialjournal

Pingback: Why rebellious workers spark great ideas – Men of Influence magazine