The Legend of Steve Jobs – His Life and Career – 4

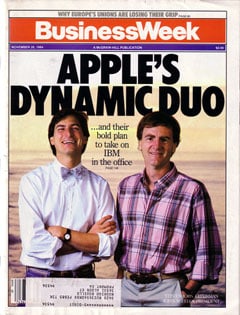

Dynamic Duo: Steve Jobs and John Sculley

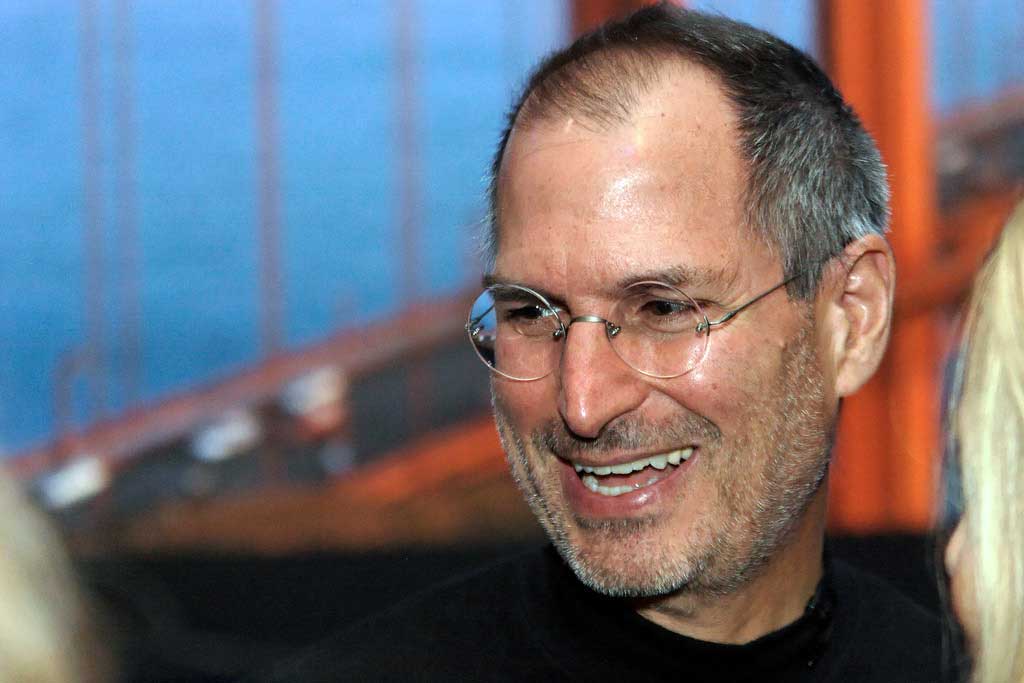

“Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life or do you want to come with me and change the world?” With this famous sentence, Steve Jobs convinced the Pepsi manager John Sculley in 1983 to enter the computer industry and move to California. But the “Dynamic Duo” did not last long. It quickly became obvious that the Apple co-founder Jobs and the new manager Sculley did not come to an agreement in key issues such as the marketing strategy for the Macintosh. It began in the time before Apple went public: In 1979, Markkula and Scott had hired the talented engineer Jef Raskin to construct a “people’s computer.”

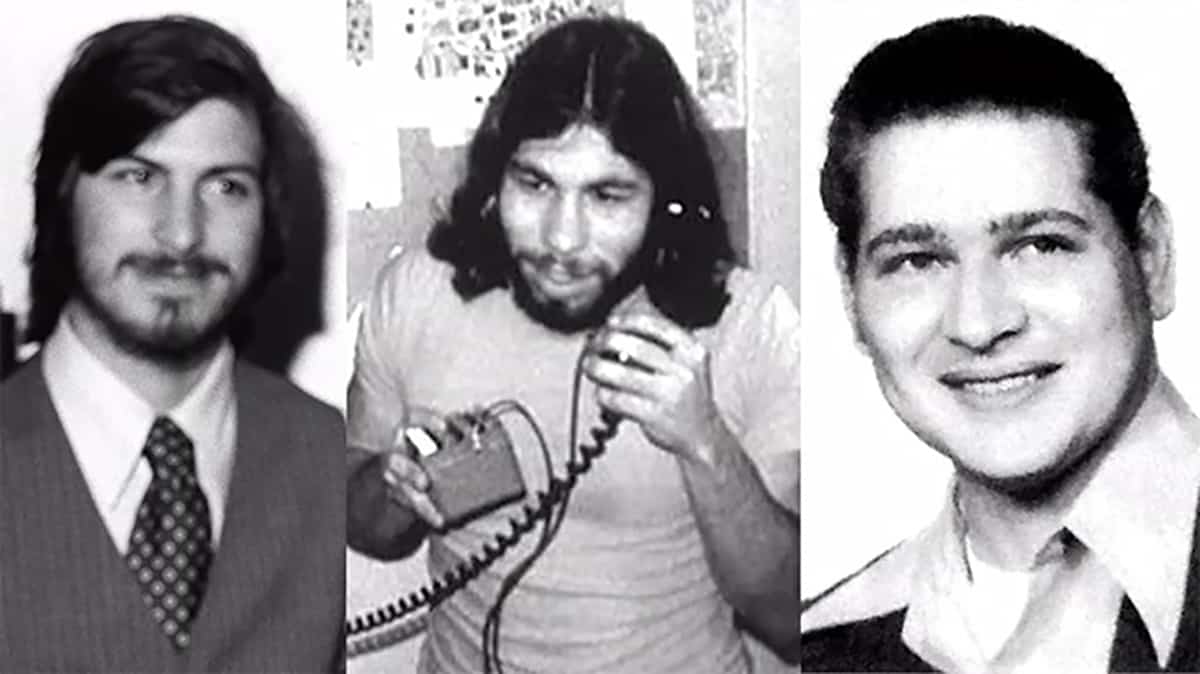

The new model should reduce the company’s dependence on mega-seller Apple II. However, the project progressed very slowly, partly because Steve Wozniak did not play an active role in its development anymore. After a plane crash with his Beechcraft Bonanza in February 1981, Woz had largely withdrawn from Apple. Therefore, it was Steve Jobs who at this stage provided strategic directions in Apple’s technology. He was neither an inventor nor an engineer or programmer. But Jobs was able to estimate the implications of new technology concepts much better than anyone else.

The Enlightenment in Xerox PARC

Steve Jobs’ masterpiece in technology scouting took off during the event of Xerox PARC. As early as 1979 he had visited with a small team of Apple developers the legendary California research center in nearby Palo Alto. He had the chance to look into the future. “They showed me really three things,” Jobs said in 1995 in a TV interview. “But I was so blinded by the first one I didn’t even really see the other two. One of the things they showed me was object orienting programming they showed me that but I didn’t even see that. The other one they showed me was a networked computer system…they had over a hundred Alto computers all networked using email etc., etc., I didn’t even see that. I was so blinded by the first thing they showed me which was the graphical user interface. I thought it was the best thing I’d ever seen in my life, ” Jobs said in a TV interview in 1995.

At Xerox PARC Steve Jobs had seen the light. Now, he also wanted to build an Apple computer that was easy to operate. Apple had bought admission to the Xerox Research Center PARC through a stock deal that appeared to be very lucrative to the narrow-minded Xerox managers on the East Coast. Xerox was allowed to buy 100,000 shares of the Apple start-up company stock before the public offering for a million dollars. In the short term, this deal was worth it: By the time Apple went public a year later, Xerox’s $1 million worth of shares were already worth $17.6 million. But in the long term, Xerox lost the chance to become an industry giant like Microsoft or IBM because the work of their researchers in California had been ignored internally.

Pirates of Macintosh

Steve Jobs was quick to distance himself from the failure of the Apple Lisa, since in 1980 the then managing director Mike Scott denied him the management of the Lisa team. In an internal competition with the Lisa team, Jobs subsequently acquired the fledgling Macintosh project from Jef Raskin and bet $5,000 that he would bring the Mac to the market before Lisa. Initially, Jobs hounded Raskin out of the group. Then he positioned his team within Apple as a rebel troop. They wanted to prove the Lisa team, which enjoyed the confidence of the management, that they could do it.

Above the building of the Mac developers “Bandley III”, a skull and crossbones flag fluttered. “It is better to be a pirate than to go to the Navy,” Jobs said to his developers. Apple investor Arthur Rock became really agitated by this action, “Flying that flag was really stupid. It was telling the rest of the company they were no good.” But Jobs loved it, and he made sure it waved proudly all the way through to the completion of the Mac project. “We were the renegades, and we wanted people to know it,” he recalled. (Isaacson, page 186)

Jobs had assembled a dream team of genius programmers and engineers, whom he urged like a cult leader with flattery and verbal attacks to continually new heights. But the ever-changing demands of Jobs delayed the Mac project so that the Apple co-founder finally lost his bet against the Lisa team. It was not until the 24th of January 1984, that the Mac was finally ready.

At the public presentation of the new computer model, Jobs recited the song “The Times They Are A-Changin” by Bob Dylan:

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won’t come again

And don’t speak too soon

For the wheel’s still in spin

And there’s no tellin’ who

That it’s namin’

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin’

In their most famous television commercials of all time, director Ridley Scott evoked this vision of enslaved IBM users who would be released through the Mac. The Mac would make clear in the clip, why Big Brother IBM would not dominate the world; why “1984 would not be 1984”. Jobs was visibly proud of the achievements they made, and attributes this to his broadly talented employees. “I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians and poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world,” Jobs said in a 1995 documentary on the U.S. television network PBS.Difficult start for the Mac

With the Macintosh, Steve Jobs had set a new milestone in computer development. But Apple had to first overcome a long dry spell in order to make a commercial breakthrough. This was also due to the fact that the first Mac model was only equipped with 128 kilobytes of main memory which was far too little. At that time, Apple Fellow Alan Kay described the Mac as a “Honda with a one-gallon gas tank.”

Furthermore, applications such as Aldus Pagemaker or peripheral devices such as laser printers, which could use the advantages of Mac GUI in desktop publishing, did not exist yet.

“The original 128K Mac had too many problems to list,” wrote Jack Schofield from the Guardian 20 years later in an article about the 20th anniversary of the apple Macintosh. “It had too little software, you couldn’t expand it (no hard drive, no SCSI port, no ADB port, no expansion slots), it was horribly underpowered and absurdly overpriced. The way MacWrite and MacPaint worked together was brilliant, but producing anything more than a short essay was a huge struggle. Just copying a floppy was a nightmare.”

In a two-day marathon meeting, Sculley demanded that Jobs should give up his position as Apple vice president and general manager of the Macintosh team. Sculley wanted Steve Jobs to become Apple’s new chairman and represent the company on the outside, without having influence on the core business. When Jobs got wind of Sculley’s plan to disempower him, he attempted to organize a coup in the Apple board. Sculley defended himself and told the board: “I said look, it’s Steve’s company, I was brought in here to help you know, if you want him to run it that’s fine with me but you know we’ve at least got to decide what we’re going to do and everyone has got to get behind it.” The majority of the board stood behind the former Pepsi manager and turned away from Steve Jobs.

Read next page: Steve Jobs loses the showdown